Métis Nation

The Métis Nation is comprised of Métis citizens who are descendants of the Historic Métis Nation. The Historic Métis Nation emerged as a distinct Nation in the Northwest in the 18th and early 19th century. They were distinct culturally, economically, and politically from their First Nation and European counterparts who lived in the Prairie provinces, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, and in Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northern United States. These areas in the provinces and territories became known as the “Historic Métis Nation Homeland”.

Geographically, the Métis Nation differs from other Aboriginal people in Canada because they do not have a land base. During the expansion of Canada westward, the Metis were dispossessed of their lands beginning in late 1860s and into the 1930s across their Homeland1.

The Métis Nation’s Citizenship is managed by the Metis Nation’s Governing Members. Currently, the Federal government has supported the establishment of Métis citizenship registries in the provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. The Métis Nation in each of these provinces, known as the Métis Nation Governing Members, have formalized a national citizenship definition that is defined as a person who self-identifies as Métis, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, is distinct from other Aboriginal people, and is accepted by the Métis Nation2.

Historically distinct Métis communities developed along the routes of the fur trade and across the Northwest within the Métis Nation Homeland. Today, many of these historic Métis communities continue to exist along rivers and lakes where forts and posts were hubs of fur trade activity from Ontario westward. As well, large numbers of Métis citizens now live in urban centres within the Métis Nation Homeland; however, even within these larger populations, well-defined Métis communities exist.

The Métis were a prominent and independent people in the 19th century and rose to resist the takeover of their homeland by the expanding Canada. Unfortunately, the immigration from Ontario, the United States and Europe was too strong and destructive, and the Métis Nation was defeated following a second resistance by Louis Riel. What followed was an enduring period of dispossession, injustice and impoverishment that caused the denigration of the Metis’ political and social structure.3

For more information on the Métis people you can consult the following organizations:

Métis National Council: www.metisnation.ca/

Métis Nation of Alberta: http://albertametis.com/

Métis Nation BC: www.mnbc.ca

Manitoba Métis Federation: www.mmf.mb.ca

Métis Nation of Ontario: www.metis.nation.org

Métis Nation Sasketchewan: https://metisnationsk.com/

1 Shore F. (2000) Eds. Barkwell L., Dorion L., & D.Préfontaine. Metis Legacy. Pemmican Publications. Winnipeg. MB. (p. 75).

2 Metis National Council website. Accessed April 22, 2016 at: http://www.metisnation.ca/index.php/who-are-the-metis/mnc

3 Manitoba Metis Federation Website, Acessed April 22, 2016 at:http://www.mmf.mb.ca/who_are_the_metis.php

British Columbia

The population of Métis people in BC was estimated at 89,000 in 2016.[1] Métis people are first documented in the province supporting early explorers: Sir Alexander Mackenzie Expedition (1793), David Thompson Expedition (1800), Simon Fraser (1805) and the Sinclair Expedition (1841, 1854.)[2]

Métis families are reported having settled in the Flathead Valley, Kootenays in 1800 and at Tete Jaune Cache near current day Valemount, BC in 1816.[3] In the early history of the province the Métis formed the first police service on Vancouver Island, the Victoria Voltigeurs. In that capacity they accompanied Royal Navy expeditions to “intimidate First Nations along the northwest coast”.[4]

Métis people played a strong role in the early colonization of the province, starting early communities and becoming landowners and political figures. “However, European newcomers and their discriminatory attitudes, in addition to a hostile legal regime in BC, forced the Métis underground but it did not extinguish our culture, history or social structures.”[5]

The Métis Nation British Columbia (MNBC), the representative organization for Métis in BC was established in 1996. The Métis Nation Relationship Accords were reached between the province of BC and MNBC. These accords called for positive working relationships and identified specific objectives related to health, housing, education, economic opportunities, Métis identification and data collection.[6]

[1] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

2] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

[3] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

[4] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

[5] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

[6] Retrieved on February 16, 2018 from the MNBC website

Alberta

Coming Soon.

Saskatchewan

Coming Soon.

Manitoba

Métis Nation in Manitoba

The languages most widely used by the Prairie Métis people were Michif-French, Michif-Cree and Bungee. The first language is a dialect of Prairie French; the second is a distinct language like no other in the world. All the nouns and associated grammar are Plains Cree. These are both very unique adaptations of the Métis people. Bungee or Bungi (see M Stobie, 1968; and E. Blain. 1989, 1994), a now extinct language, consisted of Gaelic and Cree mixed with French and Saulteaux.

The Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF) is the official democratic and self-governing political representative for the Métis Nation’s Manitoba Métis Community. The MMF promotes the political, social, cultural, and economic interests and rights of the Métis in Manitoba. It was founded in 1967 by a group of forward-thinking Métis who realized that it was necessary to stand up and fight for the rights of the Métis people of Manitoba. Decades later, the MMF has grown to over 600 staff and consists of seven Regions throughout the Province, with each of those Regions being divided into community Locals.

The Federation represents the Métis people of Manitoba and is the vehicle through which the Métis people organize politically, begin to once again manage their own affairs and re-emerge as a dynamic force in Manitoba and Canada.[1]

Struggle for Homeland and Recognition of Rights

In Manitoba, as a result of the negotiations between the Métis and the Canadian government, the Métis had secured 1,400,000 acres of land through the Manitoba Act 1870.[2] Section 31 of the Manitoba Act was supposed to secure all lands held by the Metis prior to 1870 and reserve lands for the future of Metis children. Those lands however were never lawfully distributed to the Métis. As a result, the Métis Nation did not secure a land base and were unlawfully dispossessed of their lands. The Manitoba Métis Federation launched a case against the Crown in 1981, on the basis that land promised to the Métis in the Manitoba Act 1870 was not provided in accordance with the Crown’s fiduciary obligations. In 2013, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in favour of the Métis in MMF v. Canada, and held that the federal Crown failed to implement the land grant provision set out in section 31 of the Manitoba Act, 1870.[3] The win has yet to be formally reconciled with the Crown.

Manitoba Métis Federation Regions and Locals

The MMF is organized into seven regions: Thompson, Interlake, Southwest, The Pas, Northwest, Southeast, and Winnipeg. Each region has many active locals of Métis citizens.

1] Source: Manitoba Metis Federation, retrieved on April 4, 2016 from: http://www.mmf.mb.ca

[2] Shore F. (2000) Eds. Barkwell L., Dorion L., & D.Préfontaine. Metis Legacy. Pemmican Publications.

Winnipeg. MB. (p. 7).

[3] Pape Salter Teillet LLP Barristers and Solicitors. (2013). Manitoba Metis Federation v. Canada

(Attorney General): Understanding the Supreme Court of Canada’s Decision. Accessed April 22, 2016 at:

http://www.pstlaw.ca/resources/PST-LLP-MMF-Case-Summary-Nov-2013-v02.pdf

Ontario

Métis Nation of Ontario

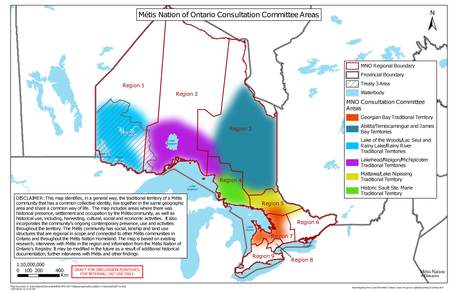

In Ontario, historic Métis settlements emerged along the rivers and watersheds of the province, surrounding the Great Lakes and throughout to the northwest of the province. These settlements formed regional Métis communities in Ontario that are an indivisible part of the Métis Nation.1

The Powley case in 2003 was foundational to establishing the rights of the Métis Nation across Canada. In 1993, Steve and Roddy Powley shot and killed a moose near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. They tagged the moose with a handwritten tag saying they were harvesting their meat for winter and did not have a hunting license.1 They were charged with being in violation of the Game and Fish Act. The Powleys pled not guilty, asserting that, as Métis, they had a right to hunt for food under Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution. The case was finally determined at the Supreme Court of Canada, with an unanimous decision as Métis people and members of a Métis community, the Powleys' right to hunt was protected by Section 35. Source: Indigenous Foundations: UBC: http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/land-rights/powley-case.html

The Powley case in 2003 was foundational to establishing the rights of the Métis Nation across Canada. In 1993, Steve and Roddy Powley shot and killed a moose near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. They tagged the moose with a handwritten tag saying they were harvesting their meat for winter and did not have a hunting license.1 They were charged with being in violation of the Game and Fish Act. The Powleys pled not guilty, asserting that, as Métis, they had a right to hunt for food under Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution. The case was finally determined at the Supreme Court of Canada, with an unanimous decision as Métis people and members of a Métis community, the Powleys' right to hunt was protected by Section 35. Source: Indigenous Foundations: UBC: http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/land-rights/powley-case.html

On April 14, 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Federal Government has Constitutional jurisdiction over Métis and Non-Status Indians. Métis and Non-Status Indians are not governed by the Indian Act, and they did not become 'Status Indians', so what this decision means for funding and services is not known, but it opens the door for a negotiated relationship that will unfold over time.5

Métis Nation of Ontario Structure

In 1993, the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) was established through the will of Métis people and Métis communities coming together throughout Ontario to create a Métis-specific governance strucure. MNO has a province-wide governance structure which includes: an objectively verifiable, centralized registry of over 18,000 Métis citizens; approximately 29 Chartered Community Councils across the province which represent Métis citizens at the local level; a provincial governing body that is elected by ballot box every four years; an Annual General meeting where regional and provincial Métis leaders are required to report back to Métis citizens yearly between elections; a charitable foundation which promotes and support Métis culture and heritage (Métis Nation of Ontario Cultural Commission); and, an economic development arm (Métis Nation of Ontario Development Corporation). 2

In 1993, the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) was established through the will of Métis people and Métis communities coming together throughout Ontario to create a Métis-specific governance strucure. MNO has a province-wide governance structure which includes: an objectively verifiable, centralized registry of over 18,000 Métis citizens; approximately 29 Chartered Community Councils across the province which represent Métis citizens at the local level; a provincial governing body that is elected by ballot box every four years; an Annual General meeting where regional and provincial Métis leaders are required to report back to Métis citizens yearly between elections; a charitable foundation which promotes and support Métis culture and heritage (Métis Nation of Ontario Cultural Commission); and, an economic development arm (Métis Nation of Ontario Development Corporation). 2

1 Source: Métis Nation of Ontario: http://www.metisnation.org/about-the-mno/the-m%c3%a9tis-nation-of-ontario/

2 Source: Métis Nation of Ontario: http://www.metisnation.org/about-the-mno/the-m%c3%a9tis-nation-of-ontario/

Northwest Territories

Northwest Territories

Coming Soon.

Video Interviews

These interviews are provided for those participants who wish to explore further the Métis experience.

Manitoba

Traditional Knowledge for Maintaining Health

Listen to Norman Meade, Métis Elder, discuss traditional knowledge for maintaining health and well-being.

Traditional Knowledge for Maintaining Health: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

The Importance of Identity

Listen to Norman Meade, Métis Elder, talk about the importance of Identity.

The Importance of Identity: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Métis Identity

Listen to Norman Meade, Métis Elder, discuss Mètis identity.

Mètis Identity: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Pressure to Assimmilate

Listen to George Fleury, Métis Elder, speak about the pressure to assimmilate.

Pressure to Assimmilate: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Hardship Growing Up

Listen to George Fleury, Métis Elder, talk about the hardship growing up .

Hardship Growing Up: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Experience of Day School and Residential School

Listen to Frances Chartrand, Health Minister, Manitoba Métis Federation, speak about the experience of day school and residential school.

Experience of Day School and Residential School: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Experience with Health Care

Listen to Frances Chartrand, Health Minister, Manitoba Métis Federation, discuss Mètis experience with health care.

Experience with Health Care: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video

Social Divide between Métis and non-Métis

Listen to Philip Beaudin, Mètis Elder, talks about the social divide between Mètis and non-Mètis.

Social Divide Between Mètis and Non-Mètis: Video

Click here to view a transcript of this video